Japanese internment survivor educates Greenwich students

By Alexandra Villarreal, Greenwich Times

Published 7:36 pm, Thursday, December 7, 2017

Photography courtesy of Bob Luckey Jr.

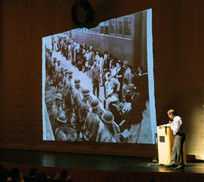

GREENWICH — When the government decided to document Japanese American internment, officials chose Dorothea Lange for a reason. Through heart-wrenching photos like the “Migrant Mother” series, she had proven her capacity to capture the humanity in tough situations and pull on viewers’ heartstrings.

GREENWICH — When the government decided to document Japanese American internment, officials chose Dorothea Lange for a reason. Through heart-wrenching photos like the “Migrant Mother” series, she had proven her capacity to capture the humanity in tough situations and pull on viewers’ heartstrings.

On the West Coast, she was asked to do just that: Manipulate public opinion. But soon, all her images were tucked away in a quiet corner of the National Archives, forgotten for decades. Her camera lens had caught the wrong kind of humanity — a reality the government would rather snuff out.

One of the photos she took was of boys clumped together, their hands over their hearts as an American flag waved in the wind. The pledge they recited claimed that in the United States, liberty and justice extend to everyone.

One of the photos she took was of boys clumped together, their hands over their hearts as an American flag waved in the wind. The pledge they recited claimed that in the United States, liberty and justice extend to everyone.

Some of the children in her picture learned otherwise.

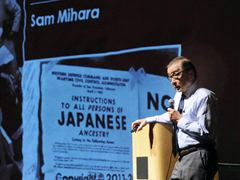

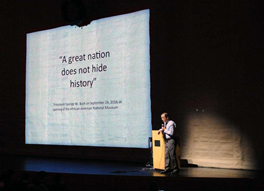

On Thursday afternoon at Greenwich High School’s Performing Arts Center, Sam Mihara scrolled through a PowerPoint filled with Lange’s photos. They were more for the benefit of his audience than to jog his memory; he did not need to study her subjects’ faces to know their story because he had lived it.

Born a U.S. citizen, Mihara was one of roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans who suffered internment during World War II. After President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942 and General John DeWitt decided to enforce it, a 9- year-old Mihara and his family were herded into buses and taken to a camp in Pomona, California.

Later, they were carried all the way to Wyoming, where they were forced to live in captivity for three years at Heart Mountain.

Later, they were carried all the way to Wyoming, where they were forced to live in captivity for three years at Heart Mountain.

Now, Mihara is sharing his experiences of persecution during World War II, and after. For a good number of Japanese Americans, the nightmare did not end with release — they came home to communities that had internalized bias against them, where they were both unwelcome and unemployable.

“I hate hatred, and that’s what affected me the most,” Mihara told an auditorium of approximately 700 sophomores studying U.S. History.

While detained, Mihara’s father went blind when doctors did not adequately treat his glaucoma, and his grandfather starved to death after a medical professional prescribed him laxatives to treat cancer. Their entire family was confined to a room that was only 20-by-20 feet, and they used public toilets that in photos appear less sanitary than a Porta-Potty.

While detained, Mihara’s father went blind when doctors did not adequately treat his glaucoma, and his grandfather starved to death after a medical professional prescribed him laxatives to treat cancer. Their entire family was confined to a room that was only 20-by-20 feet, and they used public toilets that in photos appear less sanitary than a Porta-Potty.

Still, what bothered him most were the signs in towns outside the camps that used racial slurs to condemn his existence.

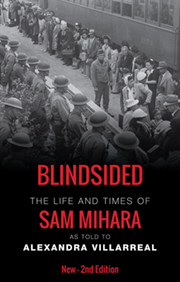

Today, Mihara — a retired rocket scientist with the Boeing Company — tours the United States to give talks at ivory towers, law firms and secondary schools. Before this week, his only Greenwich visit was along I-95, to speak at Yale.

Mihara lectured at Greenwich Country Day on Tuesday, followed by a stint at Greenwich Academy on Thursday before landing at GHS.

“The kids (will) … see the atrocities and understand the atrocities that happened in the past, and going forward as citizens that are engaged in our democracy, they’ll have the goal to be people who never want to see something like this again,” said Lucy Arecco, a GHS house administrator who coordinated the talk.

For Mihara, sharing his first-person account, as well as the knowledge he has accrued over the past half-century-plus, has become something of a mission. “I think it’s the satisfaction of teaching a topic that isn’t really being well taught in schools,” he told Greenwich Time. “I leave the audience with a real concern about the leadership of this country and the way we’re going.”

For Mihara, sharing his first-person account, as well as the knowledge he has accrued over the past half-century-plus, has become something of a mission. “I think it’s the satisfaction of teaching a topic that isn’t really being well taught in schools,” he told Greenwich Time. “I leave the audience with a real concern about the leadership of this country and the way we’re going.”

Indeed, part of Mihara’s message is to encourage people to consider that mass imprisonment of non-criminals could happen again. Recently, he has taken a particular interest in Latino undocumented immigrants and Muslims living in the United States and current policies that affect them.

During his travels, he stopped by the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas, one of three U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement facilities that house families. Though Mihara was not allowed to enter, the photos he saw and the information he heard from detainees’ attorneys floored him.

“I said, ‘This is worse than the prison I was in in World War II,’” he remembered. “It shouldn’t get any worse, and I’m starting to sense that in this country we still haven’t learned how to be humane about the treatment of people.”

Mihara’s own story had a happy ending, and he was not the only survivor who went on to contribute to American society and industry.

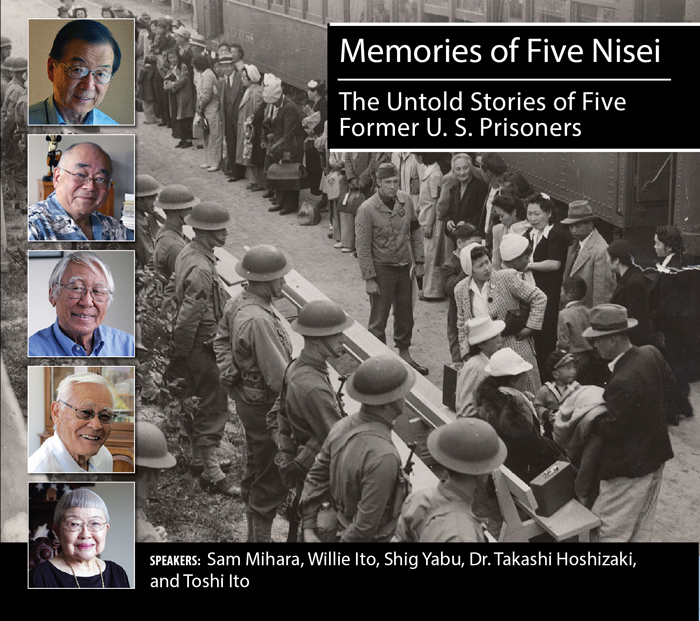

One of the boys from Lange’s photograph, Willie Ito, animated some of the country’s favorite cartoons, including “The Flintstones” and Walt Disney’s “Lady and the Tramp.”

Lance Ito, who sat on the bench during the O.J. Simpson case, was the son of two survivors who met at Heart Mountain.

But even though the judge made it in America a generation later, his relatives paid a heavy price because of anti-Japanese sentiment during and after World War II: Unable to find a job in a racist environment, Ito’s grandfather committed suicide so that the family could collect insurance to survive.

But even though the judge made it in America a generation later, his relatives paid a heavy price because of anti-Japanese sentiment during and after World War II: Unable to find a job in a racist environment, Ito’s grandfather committed suicide so that the family could collect insurance to survive.

Mihara said he wants to inform people about “the real truth of what happened during World War II, and think about the fact that it could happen again to another group.” He hopes teenagers and young adults will learn their rights and history so that when they swing by a ballot box, they understand the possible ramifications of their vote.

“You all owe it to yourselves to be responsible,” he said.